USA –– The World’s Cyber Superpower

A Cyber Superpower

The United States of America is the World’s cyber superpower.

History shows that the revolution in computing and information technology started not in the United States, but instead in England. But as the onslaught of the Second World War began to dim the starched and crusty sun of the British Empire, the world’s center of computing innovation shifted to the United States, and has never left. Today, the United States has emerged as the world’s cyber superpower. No other country comes close, in fact, the rest of the world added up together does not equal the cyberpower of the United States. Nevertheless, with cyber-greatness, comes cyber-vulnerability, and thus the United States faces many challenges going forward.

Technology Growth and Innovation

Birth of Computing. The foundations of computing were defined by Alan Mathison Turing (1912-1954), an English mathematician in his paper “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem” delivered to the London Mathematical Society in 1936. After a long discussion, he writes “If this is so, we can construct a machine to write down the successive state formulae, and hence to compute the required number.” (Don’t try to read the paper unless you know a great deal of math. A better explanation is found in Andrew Hodges book “Alan Turning: The Enigma“.)

Turing was recruited to work at Bletchley Park, the center of the UK’s codebreaking operation during the Second World War. The central challenge was learning how to break the enigma coding machine. Turing and his team built the world’s first electro-mechanical machine to break the code (bomba kryptologiczna [Polish]). Eventually the German Navy deployed an improved enigma machine with more coding rotors. This blunted the English effort.

Nevertheless, the United States Naval Computing Machine Laboratory at a secret location in Dayton, Ohio started work on a more advanced code-breaking machine using vacuum tubes. You can see a picture of the U.S. Navy Cryptanalytic Bombe at the National Security Agency’s (NSA) National Cryptologic Museum here. The Museum has a picture of coding rotors on its facebook page here. This project was located in “Building 26” on the campus of the National Cash Register Machine company. This is where the future founder of IBM worked.

Growth of Computing. The history of computing is long, but most of the book was written in the United States. In particular, the release of the IBM System 360 included the first operating system. Mainframe computers, minicomputers, personal computers, handheld computers, integrated circuits, and so on. Much of this evolution was powered by companies in Silicon Valley, but also around Route 128 in Boston. As a note, much work in development of supercomputers was funded by NSA, especially the work of Seymour Cray.

Telecommunications and Networking. Most of the world’s innovation in telecommunications and networking has occurred in the United States. There is no need here to retell the long history of developments: Telegraph, Telephone, Radio & Television, Satellite, Internet, Mobile Cellular Technology. (See Desmond Chong’s comments here.) The Internet now connects most citizens of the world. (See: Internet Society report here.) From 1992 to 2015, the number of websites grew from 10 to 863,105,652 and from 1993 the number of Internet Users grew from 108,935 to 3,185,996,155. (See Internet Live Stats.)

This growth of “cyberspace” in effect has created an entirely new virtual geography for conflict between nation states.

Control of Cyber Infrastructure. Apart from manufacturing much of the technology, US companies produce the software, cloud systems, other Internet based services, and social media systems that dominate the world. There is no European Google, for example. Companies such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft, IBM, Apple and others dominate the world’s ICT landscape.

Emergency Response to Cyber Attacks

In the Post-9/11 world, the United States has built up and incredible infrastructure to defend against terrorism and respond to it promptly once it occurs. These investments envision threats from weapons of mass destruction, lone wolf terrorist attacks, Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP), and cyber attacks. A few days after the September 11th attack, the US Congress handed over to the executive $40 billion dollars to “get started” on building these defensive systems. Then it wrote another check and another. The total amount invested is classified.

Investments were made in two direction; foreign intelligence, and emergency response in the homeland. Although the development of foreign intelligence capabilities using cyber espionage is secret, revelations from illegal criminal leaks published by the traitor Edward Snowden and the brutal Wikileaks, plus high quality yet legal investigative reporting by authors such as Dana Priest and William M. Arkin (Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State) suggest the incredible capabilities of the United States.

- A large amount of all Internet traffic worldwide is intercepted, stored, and subjected to analysis by organizations such as the National Security Agency (NSA).

- A large amount of telephony traffic is intercepted and stored, then used for analysis of a number of problems.

- Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence and other innovations in software have greatly expanded the effectiveness of intelligence analysis (although there are constant complaints that much more information is being collected than can be analyzed).

- In response to the threat of terrorism, the USA has greatly increased the integration of law enforcement and intelligence gathering and analysis by building fusion centers linking local and state resources (police; emergency response) into the Federal Government.

- The U.S. Military has been tasked with responding to threats that occur within the United States (and this requires it to collect and analyze threat data originating from within the country).

To put it in simple terms, apart from its not inconsiderable activities overseas, the United States has trained its military to fight, defend infrastructure, and collect intelligence within the United States itself.

Result: There has been a blurring of lines of responsibility between local, state, and Federal efforts to fight a cyber war.

The result is a nation state with dominant cyberpower:

- Control over the bulk of cyber technology.

- Largest and most sophisticated intelligence collection and analysis systems.

- World wide response capabilities, both kinetic and cyber, both offensive and defensive.

- The largest penetration into cyber networks around the world.

- Highest level of integration between cyber intelligence and cyber response.

Since 9/11, the United States in the cyber arena likely has invested more than 25 times as much as any nation that is in a distant second place. There is a cyber arms race, and the United States is winning, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future (providing it keeps investing, as it probably will).

What is “Cyber Power”?

It is difficult to have an undisputed definition of cyberpower, but as a starting point, we can say that for a nation state, it may be defined by the following factors:

- w1 – The number of cyber-weapons deployed and under the control of the nation-state.

- w2 – The percentage of zero day cyber weapons deployed and under the control of the nation-states.

- p1 – The maximum number of cyber warfare operators per capita that are on duty under peak deployment.

- p2 – The maximum number of volunteer or militia cyber warfare operators that may be deployed to support the government.

- Rg – The number of websites that may be attacked by government cyber fighters.

- Rp – The number of websites that may be attacked by militia cyber warfare operators.

- e1 – The number of emergency response centers dedicated to monitoring cyber attacks and coordinating response.

- e2 – The number of emergency response centers with cyber-response capabilities.

- e3 – The number of emergency response centers with capabilities to respond to secondary targets of a cyber attack, e.g., infrastructure damage, but with no cyber capabilities.

Cyberpower might be estimated as follows:

(9[w2w1]+[w1-9{w2w1}]+3.5p1+p2) * (Rg+.6Rp) + (.9e1+.4e2+.15e3)

Getting this type of data, applying proper quantification and operationalization of the relationships, however, is somewhat problematical, to say the least.

Lingering Challenges Going Forward

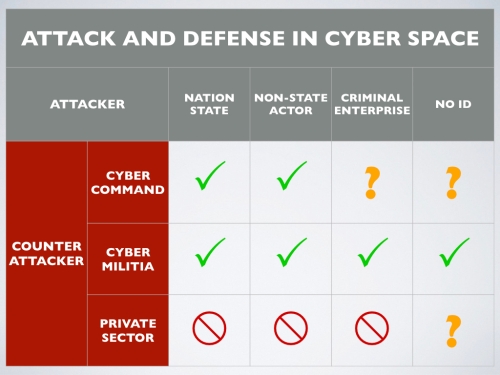

Government and Private Sector Coordination. The United States has a peculiar arrangement whereby the government is responsible for defense of the nation, but is unable to control how private enterprises, and the private sector in general, avails itself of defensive technologies. The private sector is left to defend itself. For example, Under the National Security Agency (NSA), the Cyber Command (“Cybercom”) component is responsible for development of both offensive and defensive cyber weapons. However, it is not clear at all how and under which specific circumstances the power of Cyber Command would be used. See Figure 1.

Figure 1 –– Attack and Defense in Cyberspace. The US Government (NSA’s Cyber Command) is tasked with defending the U.S. Government from cyber attacks. But in case of cyber attacks against important private sector components, including infrastructure, there is no clear role or authority.

As of 2018 Cyber Command should have a 6,200 member force. It is under the command of the U.S. Strategic Command, which also is in charge of the USA’s nuclear weapons. This number, 6,200 might possibly be only a fraction of the true size of Cyber Command, considering that it is common practice in many parts of the U.S. government, including the military, to make extensive use of outsourcing and subcontractors to get its work done. If the government employee/subcontractor ratio for other parts of the government is applied to Cyber Command, then a force of 27,900 might be more realistic.

Since it operates under the auspices of the National Security Agency (NSA), Cyber Command has responsibility for protecting the communications, including data communications and thus data processing and ICT infrastructure, of the United States Government. Presumably this means that should government ICT infrastructure come under attack from another nation state, Cyber Command could respond. The rules of cyber war are not yet worked out because it is difficult to have a “cyber war”, without any real “war”. And if there is not real “war”, then presumably government weapons would not be used to fight the conflict.

This leaves a vulnerability for the United States. If the private sector, including the USA’s vast infrastructure (electricity, transportation, finance, business process computing, communications, distribution), came under attack, it is not clear that the NSA would respond. Perhaps it has standing orders to aid the private sector, but it is difficult to see how this could happen except through the mechanism of providing warning and advice to victims of cyberattacks.

It is possible that cyber militia might be used by either the private sector or by the government, but there is not much known about this possibility, and in any case, there would be legal and regulatory barriers for this to be done by the government.

This leaves open the challenge of coordination.

Focus and Coordination. Within the U.S. government, as well as the states and local jurisdictions, a large number of fusion centers and other points of shared operational responsibility has been developed and deployed. Everything from response to a chemical biological attack to a full scale nuclear war has been prepared for. There is a particularly vigilant infrastructure in place to handle the aftermath of a severe terrorist attack against any community. But these centers specialize in different areas: some on electricity, others on public health, terrorism, or a number of other focus area. They have different degrees of cyber defense and response capabilities, if any at all.

But we can be sure that in any cyber emergency, it will be very difficult to coordinate the activities of these many centers and there is no integrated cyber response plan to do so.

Effectiveness Against Cyber Attack

So looking below at Figure 2, we might hypothesize that there is an optimum number of centers of cyber excellence that determines the level of effectiveness against a cyber attack. In the initial stages of build-up, there is a rapid rise in effectiveness. But if too much is built, the response teams will face increasing difficulty in coordinating their response, and the effectiveness will start to fall, even as investments continue to rise.

Figure 2 – Too much cyber defense might weaken the overall national efforts. Response to cyber attacks are coordinated a various national centers. As the number of these centers increases, the effectiveness of response increases, but never becomes perfect. But it never approaches perfect. At some point further increases in cyber response centers weakens national cyber defense because of the cost of coordination.

Control of the Proliferation of Cyber Weapons

Cyber Arms Control. Understanding the prospects of cyber arms control must be based on realistic assumptions about nation state motivation. when seeking international agreement, the cardinal rule is that no nation state will support any regime that does not yield it a benefit. So any international convention to control the proliferation of cyber weapons most present some advantage for each nation in acquiescence. A “win-win” scenario, to use popular game theory lingo. So from the point of view of the United States, we must examine if it is possible to identify any specific advantages from such a treaty. Here are a few to consider:

- Uncertainty Mitigation. The exchange of information between nation states, even if imperfect (as it certainly will be), will lessen the uncertainty surrounding a potential cyber attack or cyber war. This is because it will be necessary to keep a tab on the development of new cyber weapons by competing nation states. In addition, an international warning and coordination system for potential cyber war will enable the USA to better allocate the correct forces for the attack. In the absence of mutually exchanged information concerning the cyber weapons arsenals of the USA’s strategic competitors, there will be a tendency to over-build cyber-weapon counter-measures, thus wasting resources, and leading to further uncertainty. Finally, getting an insight into the cyber warfare operations and capabilities of its strategic competitors (China and Russia) will be less problematic and more accurate than obtaining an incomplete picture using traditional espionage and intelligence collection methods. In general, any regime that can lessen uncertainty in cyber war would be a stabilizing factor.

- Law Enforcement. International enforcement against cyber-based crime currently faces many serious obstacles. A short list includes: (1) extradition of cyber-criminals from one jurisdiction to another; (2) rules of evidence that are internationally recognized; (3) attribution of criminality and responsibility; and (4) variances in definitions of crimes. By putting in place the type of government-to-government coordination required for a successful cyber arms control regime, part of its function, by necessity, would be to distinguish nation-state originating weapons from other cyber abuses. Since these other abuses are by default the responsibility of criminals, this would enhance international coordination and law enforcement to bring them to justice.